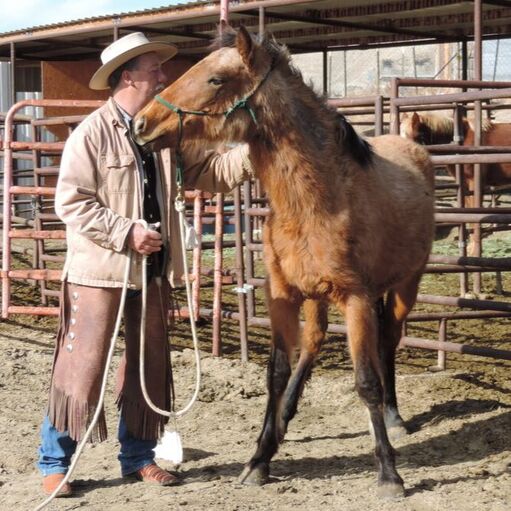

Most of us love cuddling our horses, but sometimes we fail to notice whether or not our horse is enjoying the interaction. With mustangs touching them is the first major obstacle in their educagtion. Until the mustang not only accepts being touched, but also enjoys contact with people only limited progress can be made. We may think we are rewarding a horse with a stroke, pat, or scratch, but if the horse is not enjoying that contact we are doing nothing but inflicting attentions on an unwilling participant, which is absolutely intolerable to a wild horse. For a mustang just learning about humans, any contact they find irritating will hinder their trust in people and can even lead to aggressive/defensive behaviours like striking and biting. We can all relate having handshakes that we did not enjoy at all. Crushing handshakes that make your fingers go numb, handshakes that lasted too long feeling awkward, limp finger handshakes that make you feel like you're fumbling a dead fish, and overly enthusiastic handshakes that threaten to dislocate your shoulder. None of these are pleasant, rewarding greetings and if you know someone who repeatedly greets you in one of these ways you will probably start making excuses to not shake their hand. If a poor handshake can make such a difference in how we feel about other people, just imagine the impact the way we touch a horse has on the way they feel about us. Physical contact is a highly personal thing to horses, they usually only allow their closest herdmates to have friendly contact with them. When we are touching a horse we are treading on sacred ground. Granting permission to be touched is a supreme act of trust for a mustang to extend to a person. Just as a handshake can be unpleasant in a variety of ways, a horse can find human touch intolerable in multiple ways. We can be too firm, too fast, too soft, too often, etc. How a horse likes to be rubbed is individual to each horse. Taking the time to learn where a horse likes being rubbed, stroked, and scratched is one of the best ways to build a trusting relationship, and will prevent your horse from making excuses not to let you touch them. When our touch is not enjoyable, a horse will express discomfort in small ways to let us know that the contact unwelcome. If a horse leans away from, or appears to try dodging an outstretched hand, even a tiny bit, this is a clear message that they don't want our caresses. While the horse pictured at the left is clearly not afraid of being touched, it should be also as obvious that the horse is not inviting this pet. Ears put back, a tiny bit of tension in the nostrils, the expression in the eye is a little hard, but most of all the horse is drawing away from the hand, not only with its head, but its whole body. These are subtle signs, but very important to knowing whether the horse is approving of this stroke or not. Most likely raised by humans this horse has learned to tolerate sometimes being pawed in a way that it doesn't care for. We may want to express our affection by giving big tight hugs around our horsey's neck, but most horses find this sort of contact restrictive, disturbingly predatory, and uncomfortable. Any horse that actually enjoys a big bear hug only does so as an acquired taste. Something it has learned to be comfortable with due to repetition, and because the hugs usually are coupled with pleasant things like rest from work, or treats. All horses have to learn to put up with human ineptitude to some extent or other, but we really should try our best not to annoy our horses too much. You will notice I have not used the word patted. Horses do not care for being being patted, they prefer rubbing or stroking so much more. Patting dulls their sensitivity to rhythmic pressure. Many times I have seen that the more pleased a person is with their horse the harder they pat it until it looks like they are trying to slap a fly straight through the other side of the horse's neck. In their enthusiasm to reward the horse they don't notice that the pat has turned into a physical assault and appears more like they are hitting their horse rather than giving an affectionate pat. In my opinion patting is a bad habit to get into, so just quit it already people! In contrast, how do you know if a horse is welcoming contact? The best way to explain is by showing some examples.  Notice each in each of these pictures the horses' ears are forward and they are leaning towards the human, their eyes are soft and content looking. Both photos are of mustangs that were relative new to captivity, but both look confident in the contact and have not formed a negative opinion about being touched by people. When horses are really enjoying a massage, their upper lip will twitch with pleasure. This twitching lip is the beginning of mutual grooming behaviour which is an ultimate sign of acceptance from a horse. This is the kind of interaction that horses find particularly rewarding. Dominant horses are usually the ones to initiate mutual grooming determining how intense and how long the grooming lasts. So, a mutual grooming rub builds relationship not only because you are doing something your horse likes, but it is also a subtle way to establish yourself as a higher rank in the herd. The horse at the right is returning the favour by nuzzling the person massaging him. Be cautious if your horse wants to rub on you in return, they do not know their own strength and sometimes can nip hard enough to bruise a puny human. Remember it is the dominant horse who determines the intensity of the mutual groom. Set clear boundaries of how much return rubbing you will allow, but never, never, punish a horse for wanting to return affection in this way. That would be insulting to the horse, like slapping someone's hand away when they are offering to shake with you. If the horse begins getting too vigorous in its return rubbing just quit massaging the horse(before teeth get involved) and direct the horse's nose away with a gentle push. They will get the point and learn to restrain themselves in their displays of affection. How we touch a horse is extremely meaningful to them. Even with the best of intentions we can be bothersome to a horse by not being sensitive to the way they like to be touched. Especially when trying to establish a trusting relationship with a wild horse, we need to touch them in a manner they enjoy so they will find our company comfortable and peasant.

0 Comments

It is obvious wild horses have difficulty relaxing around humans and training can be extremely stressful for them, but in order to achieve any proper learning a mustang must be calm and relaxed. To discuss ways we can teach our horses how to relax, let's look at common human relaxation techniques and how they can be applied to horses. A quick google search of relaxation techniques provided the following list:

I haven’t yet met a horse that was much of an artist, unless you count my mare who created “sculptures” with her teeth in the wood of my barn, and my horses don’t appear to enjoy my music much. I’m not an expert on what scents work well with horses for aromatherapy, although I have heard some people say it is very effective and I only wish I had the facilities to try hydrotherapy. Since I don’t have experience in those areas, I will proceed to the ones I do. Grooming, massaging, and petting your horse are all easy and highly successful ways to relax and bond with your horse. There is nothing like a good message to help calm your horse. Tai chi and yoga both use physical motion to encourage deep breathing, we can apply some of the same principles to our training to promote relaxation.There are a number of ways we can encourage our horses to take slower deeper breaths and when their breathing is relaxed their mental state will usually follow. Yoga uses stretching to open the rib cage allowing for deeper breathing. Encouraging a horse to bend and stretch not just through their neck, but all along their spine will help them achieve a more relaxed state of mind as well as improve their self carriage. Practicing lateral movements, both ridden and with groundwork will help a horse stretch and breathe. Also,because lateral maneuvers are more complex for a horse to coordinate in their body it also causes them to think more carefully about what they are doing, ergo we are helping them to “meditate”. Tai chi makes use of slow repetitions of physical movements to a relaxed meditative state. Repetition is comforting because there are no unwelcome surprises, starting and ending your training with predictable exercises your horse knows well will help them manage their emotions throughout training. Going back to those predictable exercises, or lateral stretches any time your horse's fears begin to rise is a valuable way to teach your hose to have greater self control. It cannot be emphasized enough the importance of allowing your horse time to think when training. View each task as a mental activity for your horse, even if you are asking them to learn a physical exercise, make sure you are not ignoring the mental aspect of the horse’s learning. Anything you want to teach a horse can be approached as a meditative exercise if you present the task with the least amount of pressure possible and give the horse as much time as they need to figure out what you want them to do. Relaxation is vital to a horse being able to learn. It is easiest to address the horse’s nerves before their emotions get out of control. We all know how stressful it can be associating with other people who bring negative energy, so be mindful of your own energy and emotions. Try to exude calm. Your horse will not be inclined to relax if you are tense. You also cannot help your horse’s stress level if you do not notice their mental state; one vital step to building relaxation is to pay attention. Being attuned to your horse’s emotions and giving them the tools they need to manage their stress during training will build their confidence and respect for you.  Being the sort of person who gets completely paralyzed by the fear of failing, I thought it would be a good idea to discuss the necessity of mistakes in the learning process, for both horses and humans. "Those who aren't afraid to make mistakes and allow their horses to make mistakes learn very quickly, but people who want everything to be perfect almost never get it right." I can't remember where I read this quote, but I immediately made a note of it. All too often, I find myself trying to prevent my horse from making a mistake and therefore inhibit his ability to learn to do a task using his own thinking process. I also have the bad habit of not trying new things because I am afraid of the mistakes I might make, which might end in frustration, "messing up" my horse, or maybe injury to myself. I am a worryaholic and very easily stop myself from advancing my skills. I'd like to share some thoughts from an article recently published in a PBS blog, and apply the information to my experiences with horses. A link to the blog is at the bottom of this article. The writer identified four basic types of mistakes, and I can personally say I have made them all and recognizing how they each have helped me has given me a more positive view of error. The first is "The High Stakes Mistake". This is a mistake that can involve our safety, and practically every decision we make around a horse effects our safety, so we are very justified in being afraid to make an error in judgment. It is this awareness of the risk involved with horses that has driven all of my learning. I figured that any money I spent on educating myself beat the heck out of paying for any more doctors' bills. Horses, and mustangs in particular, because they are prey animals, perceive almost everything in human world as being a threat to their safety, and therefore they are terrified of doing the wrong thing. Adding to their confusion is the fact that the right answers for living in the wild can be a deadly mistake in captivity. Fleeing is their first instinct, but running into a solid fence can have tragic consequences for a mustang. Which leads us to our next type of mistake "The Aha-Moment Mistakes". These mistakes are caused by not having enough, or the correct information. Like the wild horse that has no understanding of boundaries lacks important knowledge, when he smashes into fences. He has to process information very quickly to avoid seriously hurting himself. Not knowing what you don't know is one of the biggest dangers when working with horses. I am really surprised I have lived through many of the ignorant blunders I have made! At the same time these are also the mistakes that have been some of the best learning moments, finding out (the hard way) what doesn't work, often caused me to stumble across or search out techniques that do work. Most lapses from horses are Aha-Mistakes, a horse's view of the world is so different from our own they cannot possibly comprehend our ideas without help. If we don't give them step by step understanding of what we expect, they have no choice but to fail. When they fail, the fault is really our own for not giving them the correct preparation, or not making sure of their understanding before asking for things. The teaching/learning process is when we run into the third type of mistake "The Stretch Mistake". This mistake happens when you are trying something new or are working at improving a skill. For me it usually goes something like this: I watch some clinician with a technique I want to try. "Yipee! Fresh information! Something new to try!" I run out to my horses and discover that I am completely inept at what the clinician made look easy. I tangle my equipment, my timing is terrible, I trip over my own feet, my horses have a good laugh, or act annoyed, and I end the lesson very glad no one was watching. With practice, muscle memory takes over, the clumsiness fades and we can perform the technique with a growing level of ease, but it takes a lot of oopsies to get there. Our horses learn so much more quickly than we do. This can be both an advantage and disadvantage. Because they catch on so fast, we can fall under the misconception that their simple clumsy mistakes are "on purpose" and that they are being disobedient. Then, we can feel the need to correct, discipline, or worse, punish these honest mistakes. Horses need practice to build balance and muscle memory, just usually not as much as humans. We should keep in mind how patient our horse is with us while we fumble learning new skills before we are too harsh on their learning errors. The last type of mistake is usually what happens when we think we know it all. "The Sloppy Mistake" happens when we get lazy. It is human nature to cut corners. Some horses are willing to pick up the slack to take care of us, but sloppy horsemanship will always catch up with you eventually. A mistake, combined with something unexpected, and then mix in a lazy habit or two and you have the recipe for a very fine wreck indeed. Usually, when I reflect after things have gone very wrong, there is almost always a chain of faults, that if any one had been amended, things wouldn't have been so bad. The best, and most irritating, thing about sloppy mistakes is that they are totally preventable. One simply needs to pay attention, and practice proper horsemanship. Some horses have a greater tendency towards sloppy laziness than others. In my opinion most horses desire to please their human partners. If we accept laziness that is all we will get. So, lazy mistakes on the part of the horse are a reflection of the rider/handler, this should make us mindful of the fact that we need to be observant, yet not overly critical of, not only our own faults, but that of our horses too. In the end when we choose to handle horses we make ourselves responsible for both our own mistakes and theirs by how we teach and interact with them. Keeping a healthy attitude toward mistakes is vital to continually improving our horsemanship. Below is the link to the PBS article, for those of you who are interested in reading more. http://ww2.kqed.org/mindshift/2015/11/23/why-understanding-these-four-types-of-mistakes-can-help-us-learn/  We live in a world where a “papered” horse is a good horse, where recognizable names on a pedigree can add thousands of dollars to a purchase price, and bloodlines are a ticket to a life of greatness. But could we be formulating the outcome of a horse’s life based on our thoughts and not on its actual ability? Can you place the same expectations on a no-name grade horse with decent conformation and get similar results? That is proving to be more and more true. Every horse is bred for success given the right opportunity. Take the famous Snowman for example. A former plow horse plucked out of a truck headed to slaughter and went on to be top Open Jumper in the United States two years in a row in the 1950s. More recently, a three-strike mustang named Cobra has won a World Championship in USEF Western Dressage. This isn’t just dumb luck. These horses were fortunate enough to have ended up in the hands of humans who offered them opportunity. When we work with our horses, it’s important not to set them up for failure with pre-conceived notions, such as “Hancock bred horses are stubborn”, or “blue-eyed paints are crazy”. These stereotypes will set you up to receive what you expect. It will cause you to treat that horse in a way that is hasn’t deserved, and could possibly lead to behaviors you are trying to avoid. Instead, if we really listen to the horse and let us know where it’s sensitivities are, we will get to its potential much faster. Why do so many horses end up in slaughter or in dire situations? I believe it is because they weren’t given the opportunities to be valuable to the humans responsible. Think about that when you come across a reactive horse who wasn’t given patience, or a dull horse who has shut down from being beat on and not knowing what to do to relieve the pain. Proper training is the best method of developing a good-minded horse. Why are we blaming these horses when we should be blaming their history? Give that horse a chance and you won’t be disappointed. KATHERINE JOHANSONAPRIL 28, 2020  "Always end on a good note." I have heard that advice repeated again and again. While it is excellent advice, many people(myself included) struggle to follow it. So, what does it really mean to end a lesson on a good note? What if you can't see any improvement in the lesson you are trying to teach, how can you still end on a good note? And the hardest one for me: How do you avoid over-doing a lesson to end at a favourable time? The first problem we have in finding a positive place to end a lesson is that we are looking at the lesson in human terms. We want to see tangible improvement in the horse's behaviour or increased skill in performing a task, but those things are not important to the horse. A horse does not care if it has learned to yield its haunches and forequarters with equal lightness, or made a nice halt-canter transition, or any of the other myriad of nit-picky tasks we grade horses on. These tasks humans invent for horses are not vital to a horse's survival and therefore difficult for horses to understand. What a horse does care about is finding comfort and safety. When a horse feels safe and comfortable they then it will want to play, figure out puzzles, and interact with their environment in new ways. Seeking comfort and the desire for entertaining stimulation are the reasons why horses do all the crazy exercises we come up with for them. They can only understand a that we have ended the lesson "on a good note" if they are feeling relaxed. If the horse finally executes a move correctly and you end the lesson, if the horse was not calm and engaged when they did it, they are not likely to remember what was correct from the human's view. Being sure that the horse is calmer at the end of the lesson is a good way to be sure that you have found what the horse will see as a positive stopping point, regardless of whether or not the task was done perfectly or not. The best time to end a lesson would of course be when the horse improves in its ability while gaining relaxation at the same time. Within a lesson there are many good stopping points. Transitions from one exercise to another should be considered a stopping point as you are quitting one task to start another. Isolating the exercises by giving your horse a rest between activities helps them retain the lesson. The best time to switch tasks is when the horse has shown improvement, not perfection! You can come back to the same task several times in a lesson or on another day, but breaking it up with rests and other exercises will keep your horse motivated and not feeling drilled. A saying I love is: "ride for tomorrow". Look for tiny improvements that you can build on in your next lesson. Getting it done exactly right in this lesson isn't important, but stopping at a place where your horse feels like they understand and have been successful is. Even the best trainers can have lessons turn into unmitigated disasters! There are times that no matter what you do the lesson does not improve; the horse won't do what is being asked and does not get calmer. In that case the time to stop is before the lesson spirals out of control. If it appears that things are not going to get any better it is preferable to end the lesson than ingrain the horse with negative associations concerning the exercise. Still, quitting the lesson at a favourable point is important. If that means quitting an exercise or lesson to stand with your horse while they graze, or taking them back to the barn for grooming, it is still ending on a positive note. At the end of the day, parting as friends is the best note you can end on with your horse. |

AuthorTrainers and mustang owners sharing their experiences and insights about mustangs. Archives

November 2022

Categories

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed